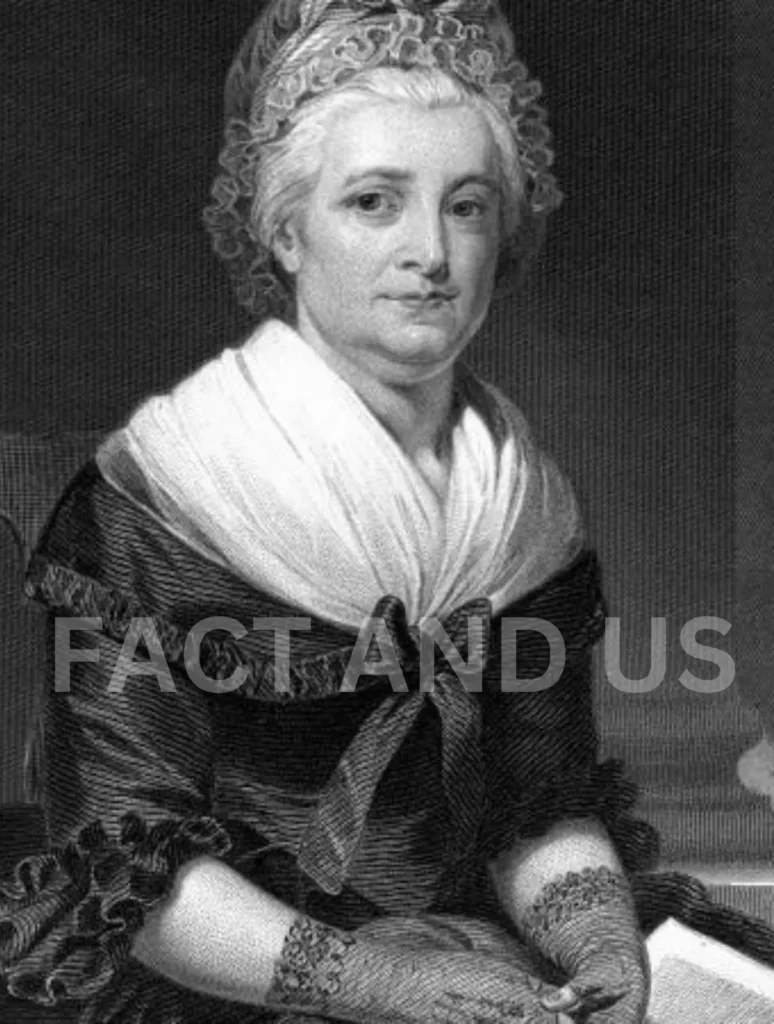

Martha Washington (born June 2, 1731, New Kent county, Virginia [U.S.]—died May 22, 1802, Mount Vernon, Virginia, U.S.) was the American first lady (1789–97), the wife of George Washington, first president of the United States and commander in chief of the colonial armies during the American Revolutionary War. She set many of the standards and customs for the proper behaviour and treatment of the president’s wife. Daughter of farmers John and Frances Jones Dandridge, Martha grew up among the wealthy plantation families of the Tidewater region of eastern Virginia, and she received an education traditional for young women of her class and time, one in which domestic skills and the arts far outweighed science and mathematics. In 1749, at age 18, she married Daniel Parke Custis, who was 20 years her senior and an heir to a neighbouring plantation. During their life together she bore four children, two of whom died in infancy. Her husband’s death in July 1757 made her one of the wealthiest widows in the region.

Contents

- 1 Martha Washington

- 2 Martha Washington at Mount Vernon, lithograph by Jacob Rau, c. 1868.

- 3 Early Life (1731–1748)

- 4 Marriage to Daniel Parke Custis (1749–1757)

- 5 First lady, wife of the president of the United States.

- 6 Personal Life

- 7 American Revolution (1775–1789)

- 8 Independent United States

- 9 Later life and death (1797–1802)

- 10 Legacy

- 11 Honors

- 12 Historian Assessments

Martha Washington

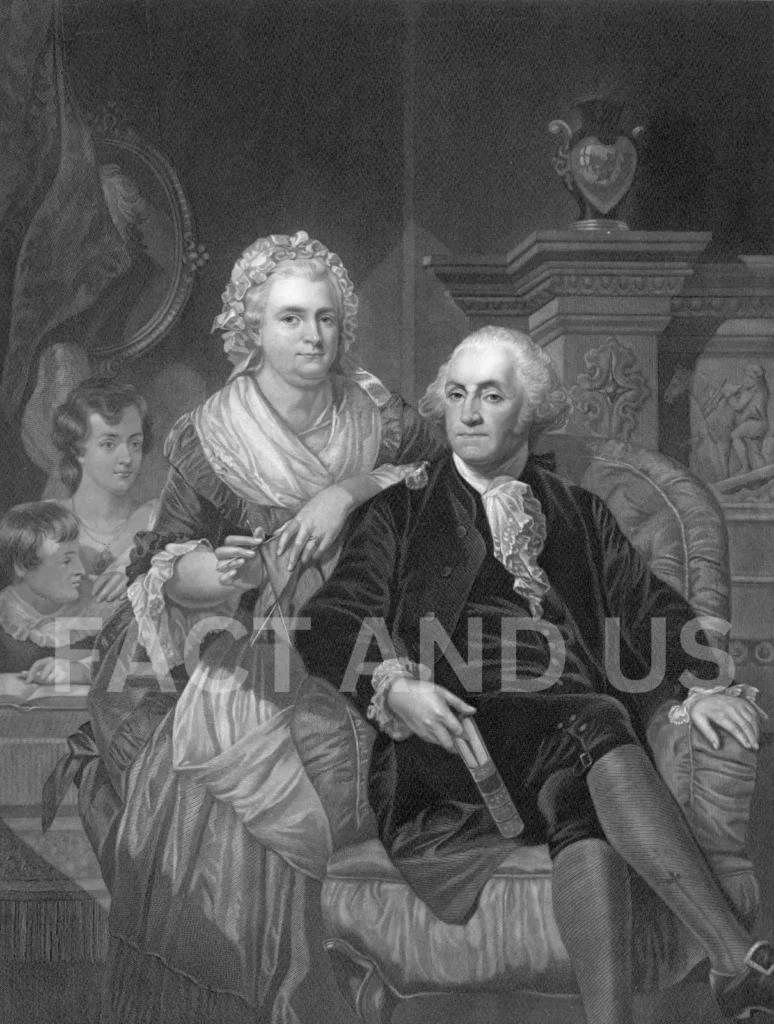

In the spring of the following year George Washington, then a young plantation owner and commander of the Virginia forces in the French and Indian War, began to court her, and their attachment grew increasingly deep. The couple married at Martha’s home on January 6, 1759, and she and her children joined Washington at Mount Vernon, his plantation on the Potomac River. Washington later resented suggestions, which were undoubtedly true, that his wife’s considerable property had eased his life in the early years of their marriage.

Martha Washington at Mount Vernon, lithograph by Jacob Rau, c. 1868.

At Mount Vernon Martha became known for her graciousness and hospitality. After George was chosen to command the American forces in the Revolutionary War, Martha spent winters with him at his various military quarters, where she lived simply and encouraged other officers’ wives to help in the war effort by economizing and assisting their husbands. After the war, during which her only surviving son died, Martha virtually adopted two of her grandchildren, and they substituted in many ways for the children she and George never had.In 1789, shortly after her husband’s inauguration as president of the United States, Martha joined him in New York City, then the national capital. Martha was widely hailed and often feted along the route, and she became known to Americans as “Lady Washington.” The couple’s rented home on Broadway also served as the president’s office, exposing her to her husband’s callers and drawing her into political discussions more than would have been the case had home and office been separated. When Philadelphia became the seat of government in 1790 and the Washingtons moved to a house on High Street, Martha’s hospitality became even more elaborate. The first lady took no stands on public issues, but she was criticized by some for entertaining on a scale too opulent for a republican government, and she was only too glad to retire to Mount Vernon after her husband completed his second term of office in 1797.

Following George’s death in 1799, Martha continued to reside at Mount Vernon. In 1800 Congress granted her a lifetime franking privilege, which it continued to grant to any president’s widow who applied for it. After Martha died in 1802, there was considerable discussion in Congress about burying the Washingtons in the capital city that bore their name, but instead she was buried beside George in a family tomb at Mount Vernon.

Early Life (1731–1748)

Martha Dandridge was born on June 2, 1731, on her parents’ tobacco plantation in Chestnut Grove Plantation in New Kent County the Colony of Virginia. She was the oldest daughter of John Dandridge, a Virginia planter and county clerk who immigrated from England, and Frances Jones, the granddaughter of an Anglican rector. Martha had three brothers and four sisters: John (1733–1749), William (1734–1776), Bartholomew (1737–1785), Anna Maria “Fanny” Bassett (1739–1777), Frances Dandridge (1744–1757), Elizabeth Aylett Henley (1749–1800), and Mary Dandridge (1756–1763). As the oldest of eight, including one sister that was 25 years her junior, Dandridge played a maternal and domestic role beginning early in life. Dandridge may have also had an illegitimate half-sister born into slavery, Ann Dandridge Costin, and an illegitimate white half-brother, Ralph Dandridge.

Dandridge’s father was well-connected with the Virginia aristocracy despite his relative lack of wealth, and she was taught to behave as a woman of the upper class. She received a relatively high quality education for the daughter of a planter, though it was still inferior to that of her brothers. She took to equestrianism, at one point riding her horse up and down the stairs of her uncle’s home and escaping chastisement because her father was so impressed by her skill.

Marriage to Daniel Parke Custis (1749–1757)

In 1749, Dandridge met Daniel Parke Custis, the son of a wealthy planter in Virginia.They wished to marry, but the father of Dandridge’s prospective groom, John Custis, was highly selective of what woman would marry into the family’s fortune. She eventually won his approval, and Dandridge married Custis, who was two decades her senior, on May 15, 1750. After they were married, Custis moved with her husband to his residence at White House Plantation on the Pamunkey River. Here they had four children: Daniel, born 1751; Frances, born 1753; John, born 1754; and Martha, born 1756. Daniel died in 1754 and Frances died in 1757. Daniel Parke Custis was one of the wealthiest men in the Virginia colony as well as one of the largest slaveowners, owning nearly 300 slaves.

Custis became a widow at the age of 26 when her husband died (possibly from a severe infection of the throat).Upon his death, she inherited the large estate that he had previously inherited from his father. After his death in 1757, she received one third of his estate outright, and the remaining two thirds were granted to their two young children. The total inheritance amounted to approximately $33,000 (equivalent to $1,104,439 in 2023), 17,000 acres of land, and hundreds of slaves. The legal and financial matters of the inheritance presented a considerable burden on Custis while she was raising her two surviving children and grieving the loss of her husband and her children as well as that of her father. She was also left with the responsibility of managing the farmland and overseeing the well-being of the slaves. According to her biographer, “she capably ran the five plantations left to her when her first husband died, bargaining with London merchants for the best tobacco prices”.

First lady, wife of the president of the United States.

Although the first lady’s role has never been codified or officially defined, she figures prominently in the political and social life of the nation. Representative of her husband on official and ceremonial occasions both at home and abroad, the first lady is closely watched for some hint of her husband’s thinking and for a clue to his future actions. Although unpaid and unelected, her prominence provides her a platform from which to influence behaviour and opinion, and popular first ladies have served as models for how American women should dress, speak, and cut their hair. Some first ladies have used their influence to affect legislation on important matters such as temperance reform, housing improvement, and women’s rights. Although the wife of the president of the United States played a public role from the founding of the republic, the title first lady did not come into general use until much later, near the end of the 19th century. By the end of the 20th century, the title had been absorbed into other languages and was often used, without translation, for the wife of the nation’s leader—even in countries where the leader’s consort received far less attention and exerted much less influence than in the United States.

Personal Life

The first presidential residence was a house on Cherry Street, followed by a house on Broadway. The capital was moved to Philadelphia in 1790, and the presidential residence again moved, this time to a house on High Street (now Market Street). Washington much preferred the Philadelphia residence, as it had a greater social life and was closer to Mount Vernon. Early in her husband’s presidency, she had little opportunity to go out, as any action she took would have political implications. After their move to Philadelphia, the Washingtons loosened their self-imposed limits on personal activity. While serving as first lady, Washington became close to Polly Lear, the wife of her husband’s secretary Tobias Lear. She also associated with Lucy Flicker Knox, wife of war secretary Henry Knox, and Abigail Adams, the second lady. The time she spent with her grandchildren was another high point for Washington, who would sometimes take them to shows and museums. She also made a point of frequently attending church, owing to her firm Episcopalian beliefs.

Washington was forced to take control of the presidential residence at one point shortly after her husband’s presidency began, forbidding guests from entering, as he was undergoing the removal of a tumor. In July 1790, artist John Trumbull gave Washington a full-length portrait painting of her husband as a gift. It was displayed in their home at Mount Vernon in the New Room. When Washington learned that her husband might take on a second term as president, she uncharacteristically protested against the decision. Despite her opposition, he was reelected in 1793, and she reluctantly accepted four more years as the wife of the president. The young Georges Washington de La Fayette joined the Washington family in 1795 while his father, Marquis de Lafayette, was held as a political prisoner in France. He would live with the Washingtons until fall of 1797. In 1796, Washington’s slave and personal maid Onley Judge escaped and fled to New Hampshire. Despite Washington’s insistence to her husband that Judge should be returned and again should be Washington’s slave, the president did not attempt to pursue Judge. Washington’s tenure as first lady ended in 1797.

American Revolution (1775–1789)

Early revolution

Life for the Washingtons was interrupted as the American Revolution escalated in the 1770s. Though rumors were spread that she was a Loyalist, Washington consistently shared her husband’s political beliefs. She strongly supported his role in the Patriot movement and his work to advance his beliefs in the cause. She stayed at Mount Vernon when he was appointed commander-in-chief of the Continental Army in 1775, overseeing the construction of new wings to their home. She then moved to the home of her brother-in-law so as not to be so conspicuous a target during the American Revolutionary War.

The revolution was the first time in their marriage that they were apart for an extended period. In the fall of 1775, Washington traveled to Massachusetts to meet with her husband. On the journey north, she experienced her newfound celebrity status for the first time as the wife of a famed general. She joined him in Cambridge, from where he and the other Continental Army officers were operating. While staying in Cambridge, she served as a hostess for guests of the officers.4 She would also sew clothes for the soldiers while at camp, encouraging other officers’ wives to do the same, leading to the creation of a sewing circle that contributed to the war effort. Though she hid it from those around her, Washington was frightened by the gunfire that could be heard from the nearby Siege of Boston. She accompanied her husband when operations were relocated to New York, but she was sent to Philadelphia as British forces came closer. Each spring, when conflict resumed, she returned to Mount Vernon.

Independent United States

The American Revolution became increasingly stressful for Martha after the signing of the Declaration of Independence, as George faced increased risks on the battlefield. Each winter, Washington would join her husband at his encampment while fighting was stalled. The quality of her housing varied during these visits, both in comfort and in safety. General Lafayette observed that she loved “her husband madly”. Washington was kept informed of the war’s developments by her husband, sometimes performing clerical work for him, and she was even permitted to know military secrets. She became a symbol of the war effort, alongside George Washington, as a grandmotherly figure that cared for the soldiers.

The Continental Army settled in Valley Forge, the third of the eight winter encampments of the Revolution, on December 19, 1777. Washington traveled 10 days and hundreds of miles to join her husband in Pennsylvania. On April 6, Elizabeth Drinker and three friends arrived at Valley Forge to plead with the General to release their husbands from jail; the men, all Quakers, had refused to swear a loyalty oath to the American revolutionaries. Because the commander was not available at first, the women visited with Martha. Drinker described her later in her diary as “a sociable pretty kind of Woman”.

Later life and death (1797–1802)

The Washingtons left the capital immediately after the inauguration of John Adams, making the return journey to Mount Vernon, which by then had begun to decay. Again they went into retirement, and they saw to several renovations for their home. In the years after the presidency, the Washingtons received more visitors than ever, from friends and strangers alike. They eventually took in one of the former president’s nephews, Lawrence Lewis, to serve as secretary, and he would eventually marry Washington’s granddaughter Nelly.

Washington feared that her husband would again be called away to lead a provisional army against France, but no such conflict took place. Her husband died of a severe throat infection on December 14, 1799 at the age of 67.As a widow, Washington spent her final years living in a garret where she knitted, sewed, and responded to letters. Though she was the legal owner of her husband’s property, she gave control of its business affairs to her relatives. She also inherited her husband’s slaves on the condition that they be freed upon her death. Fearing that these slaves might hurt her, she freed them. She did not have the authority to free her dower slaves, and she chose not to free the one slave, Elish, whom she personally owned.

Washington retained an interest in the presidency after her tenure as first lady, beginning the tradition of advising her successors. The Washington family long disliked Thomas Jefferson and Jeffersonian politics, in part because of the central role he played in criticizing the Washington administration. Washington took offense when Jefferson became president, as she felt that he did not give adequate respect to the office.

Tomb of George Washington (Right) and Martha Washington (Left)

Washington’s health, always somewhat precarious, declined after her husband’s death.[29] She had anticipated her death since that of her husband. When she developed a fever in 1802, she burned all of her husband’s letters to her, summoned a clergyman to administer last communion, and chose her funeral dress. Two and a half years after the death of her husband, Washington died on May 22, 1802, at the age of 70.Following her death, Washington’s body was interred in the original Washington family tomb vault at Mount Vernon. In 1831, the surviving executors of George’s estate removed the bodies of the Washingtons from the old vault to a similar structure within the present enclosure at Mount Vernon.

Legacy

Just as her husband had set the precedent for the presidency, Washington established what would eventually become the role of first lady. She was prominent in the ceremonial aspects of the presidency, assisting her husband in his role as head of state, but she had very little public involvement in his administrative role as head of government. This would be the standard of presidential wives for the next century. Washington was recognized for her humility and her mild-mannered nature, to the point that her contemporaries were often taken by surprise when meeting her. No personal records of Washington exist from before the death of her first husband, and she destroyed many letters that she had written since then. Many recipients of her letters kept them, however, and those letters have been preserved in archives such as at Mount Vernon and the Virginia Historical Society. Several collections of these letters have been published.

Honors

During the Revolutionary War, one of the regiments at Valley Forge named themselves “Lady Washington’s Dragoon” in her honor. The Martha Washington College for Women was founded in Abingdon, Virginia in 1860.It was merged with Emory & Henry College in 1918,and the main original building of Martha Washington College was converted to the Martha Washington Inn. Martha Washington Seminary, a finishing school for young women in Washington, DC, was opened in 1905,and it ceased operations in 1949.

A postage stamp featuring Martha Washington, the first stamp to honor an American woman, was issued as part of the 1902 stamp series. An 8-cent stamp, it was printed in violet-black ink. The second stamp issued in her honor, a 4-cent definitive stamp printed in yellow-brown ink, was released in 1923.A 1+1⁄2-cent stamp was issued in 1938 to honor Washington as part of the Presidential Issue series. Washington’s image was featured on the one dollar silver certificate banknote beginning in 1886, making her the second woman to appear on an American banknote after Pocahontas. To prevent confusion with existing coinage, pattern coins testing new metals have been produced by the U.S. mint, or a company contracted to it, with Martha Washington on the obverse.

Historian Assessments

Since 1982 Siena College Research Institute has periodically conducted surveys asking historians to assess American first ladies according to a cumulative score on the independent criteria of their background, value to the country, intelligence, courage, accomplishments, integrity, leadership, being their own women, public image, and value to the president.[42] Consistently, Washington has been ranked in the upper-half of first ladies by historians in these surveys. In terms of cumulative assessment, Washington has been ranked:

9th-best of 42 in 1982

12th-best of 37 in 1993

13th-best of 38 in 2003

9th-best of 38 in 2008

9th-best of 39 in 2014